Maths & Music #8: Temporal and formal thinking

“How do you go from mathematics to the subject of music? ” Here's the latest article in our Maths & Music column proposed by Núria Giménez Comas, composer and former mathematics student, and José L. Besada, musicologist and section editor for the Journal of Mathematics and Music from 2020 to 2023.

This text presents an interaction between the composer (italic script) and the musicologist (Roman script).

José L. Besada: “I think the issues of representing musical ideas, and in particular compositional thought, emerge as fundamental research topics. This cognitive perspective led me to take part in the SMIR and ProAppMaMu projects, led by Moreno Andreatta, who has already presented his approach in the first issue of this series of popular articles. Thanks to cognitive science, we began to explore how we interact with certain geometric representations of music theory, such as the Tonnetz.

At the same time, I was conducting personal research into the musical representations of time by contemporary composers. During my visits to the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel, the world's largest archive of documentation on 20th and 21st century composers, I came across singular sketches for geometrically drawing time, ranging from Pierre Boulez 's smooth/sorted time dichotomy to the spirals and helicoids of so-called spectral music composers (notably Gérard Grisey and Kaija Saariaho). Similarly, in the archives of composer Iannis Xenakis, I found drawings of cogwheels representing rhythmic interactions thanks to his cribles, a creative strategy combining Boolean algebra and modular arithmetic. My take on these subjects borrows notions and methodologies from cognitive linguistics; in the case of mathematically inspired music, the perspective of George Lakoff and Rafael E. Núñez is always a source of learning.

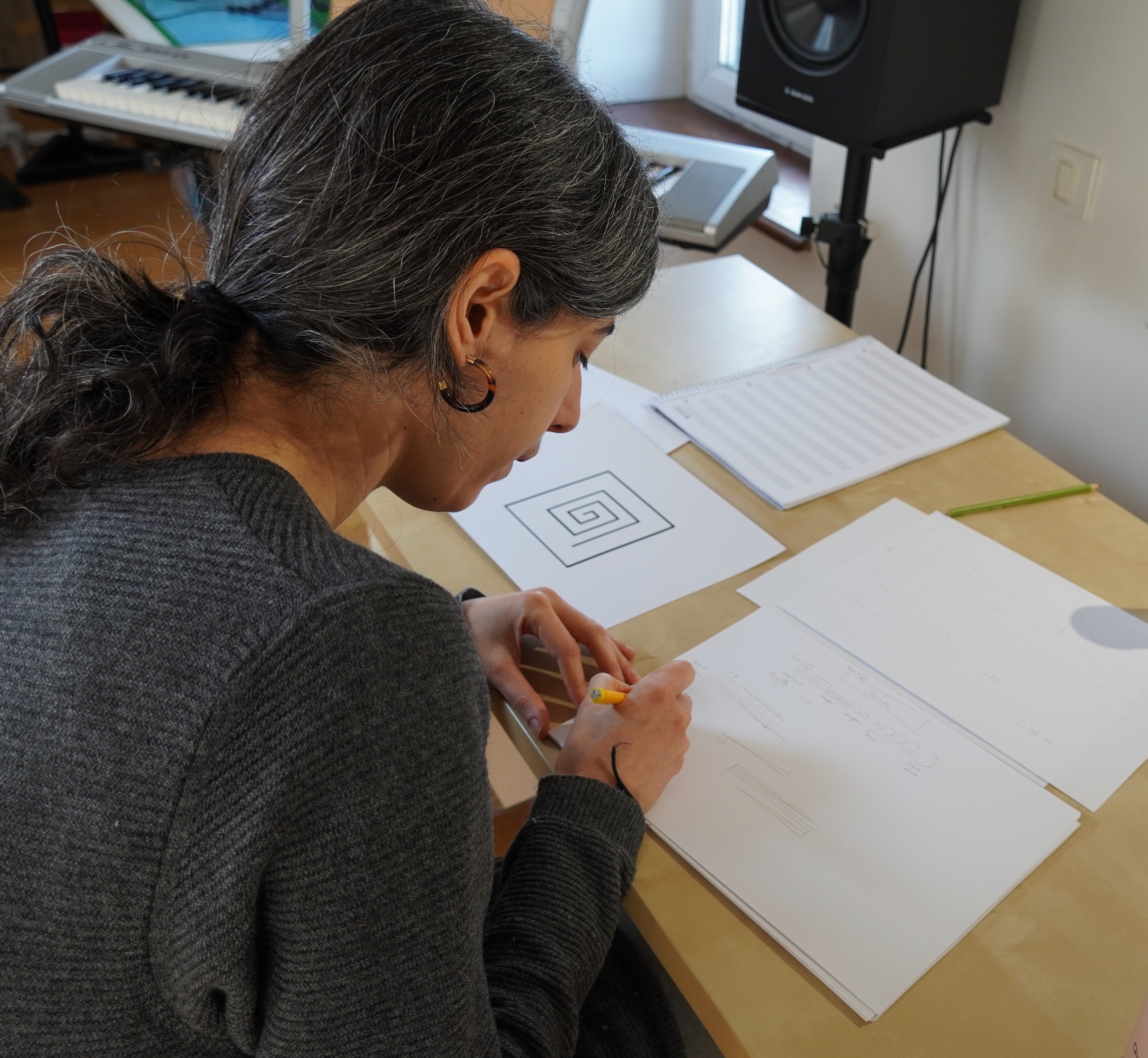

This background encouraged me to apply in 2023 for the BBVA Foundation's “Leonardo Scholarship” in Spain. I was accepted thanks to my 3C-TEMPO project. This enabled me, on the one hand, to take another look at some of the Paul Sacher Foundation's funds. Secondly, I commissioned three new musical pieces, for percussion trio with optional electronics, from composers Abel Paúl and Rafael Murillo Rosado and composer Núria Giménez Comas. My aim was to follow their musical practices ethnographically and auto-ethnographically. In our first meeting, I proposed a controlled cognitive experiment based on sketches by other female composers and (see Figure 1). Clearly, this prelude had a particular impact on Núria Giménez Comas's creative thinking...”.

Núria Giménez Comas: “The subject of time as a raw material prompted me, before and after writing, to evoke these intermediate passages on temporal writing (smooth time / striated time and also linked to the play and perception of different types of writing). In the first experiments of a musicological nature, graphs were at the heart of the research to imagine small musical “sketches” based on these graphs. This highly enriching experience led me to discover graphs such as the spiral that formally constituted Saariaho'spiece Nymphéa (1987), as well as Grisey's research into temporality (and different types of writing).

In the idea of creating a new poetic piece, I really wanted to reflect strongly contrasting temporal extremes, inspired by the contrast (so difficult to imagine) of observing the sky and events on earth. I find that the film Nostalgia de la luz (2010) powerfully explains this: the search for the bones of lost beings among the stones of the desert, while astronomers watch the sky closely.

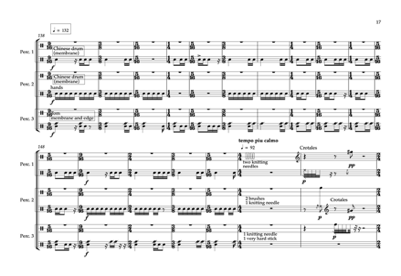

For the different types of writing in the piece, the transition from one type of cut-and-count writing to another, based on gesture and resonance (proportional graphics) becomes interesting. The poetic idea of the piece Pedres, llàgrimes sospeses (2024) is linked to these different dramaturgical temporalities, and also to its relationship with space. When working with space, on the one hand I visualize and draw geometric diagrams in a timeline, and on the other I adapt the ideas, always utopian at the outset, to the musical materials and sometimes to a space that can be shaped or adapted.

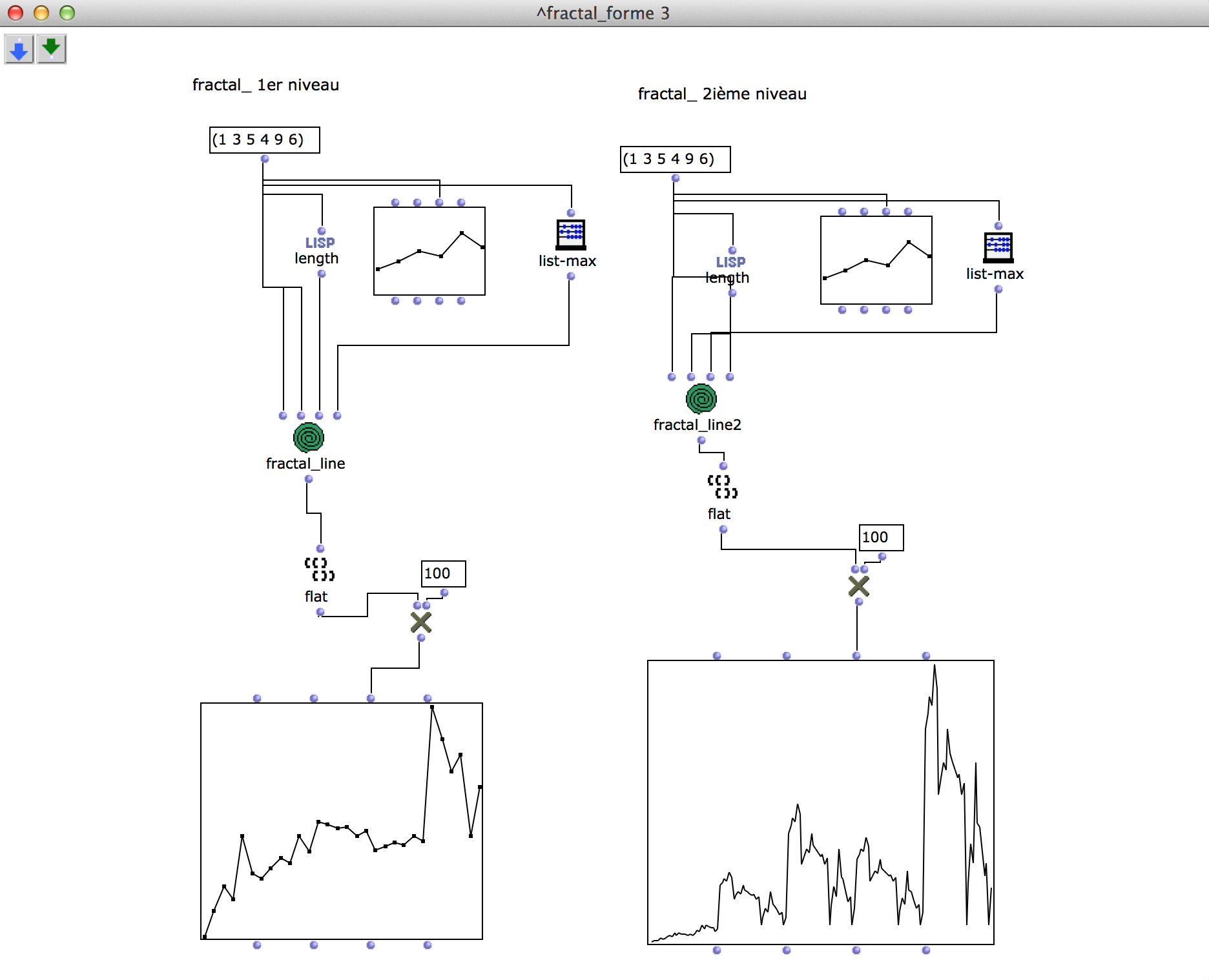

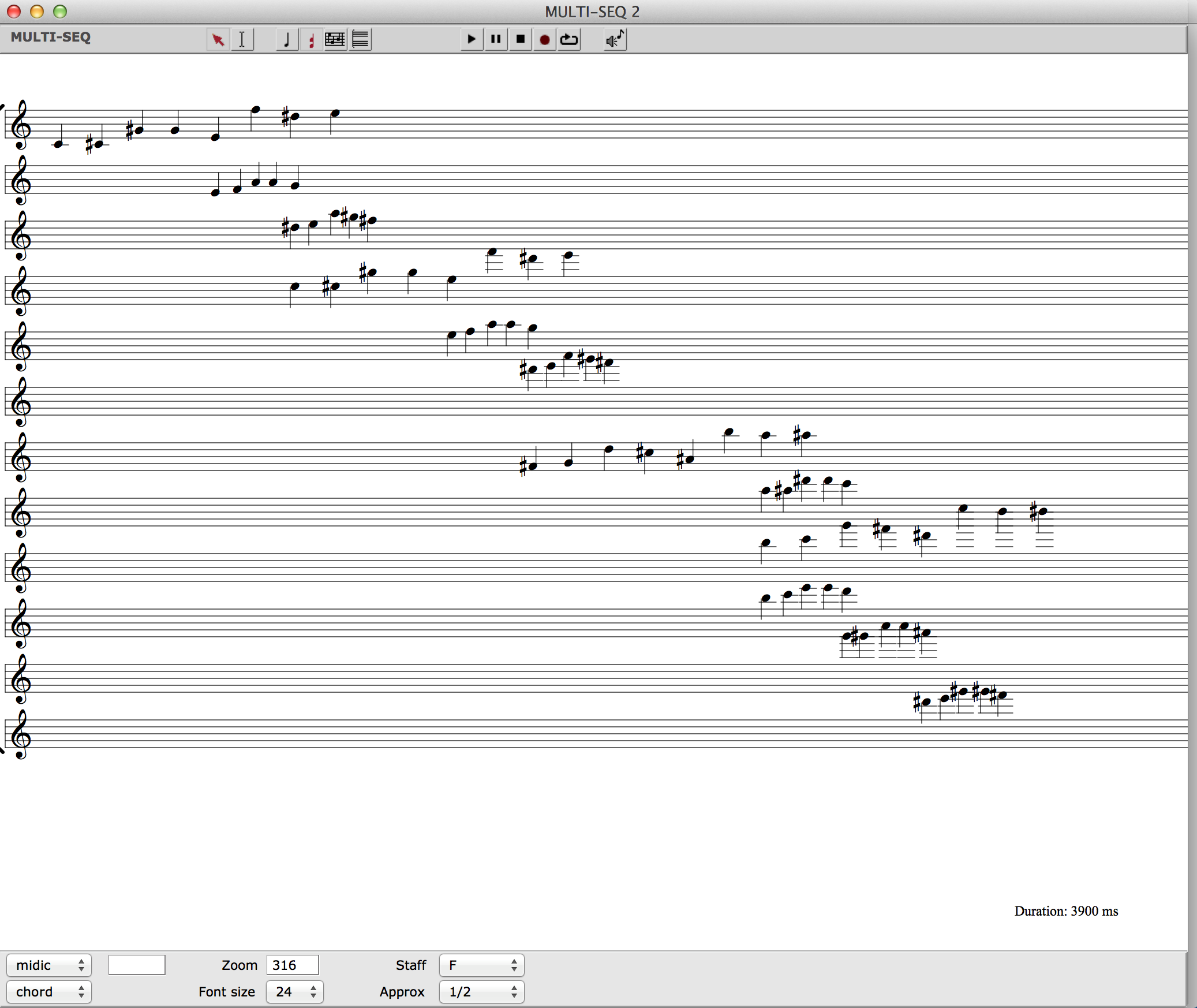

Using temporal material as the basis for the work's composition, the ideas of periodicity and aperiodicity were at the heart of the piece's development, working on superimposed processes that are sometimes continuous, sometimes discontinuous. I reviewed the representations on OM (Open Music, IRCAM's software dedicated to assisted musical composition) of the ideas of cycles, temporal sub-division and its representations, either in the writing or in graphs (see Figure 2). Still with the idea of moving from these mathematical ideas to musical material, I had in the past tackled the idea of fractal imagery using the property of self-similarity in musical gesture-phrasing, here's an example of an OM patch that was used for the piece Abraxas ( 2013) with video artist DanBrowne.

|

|

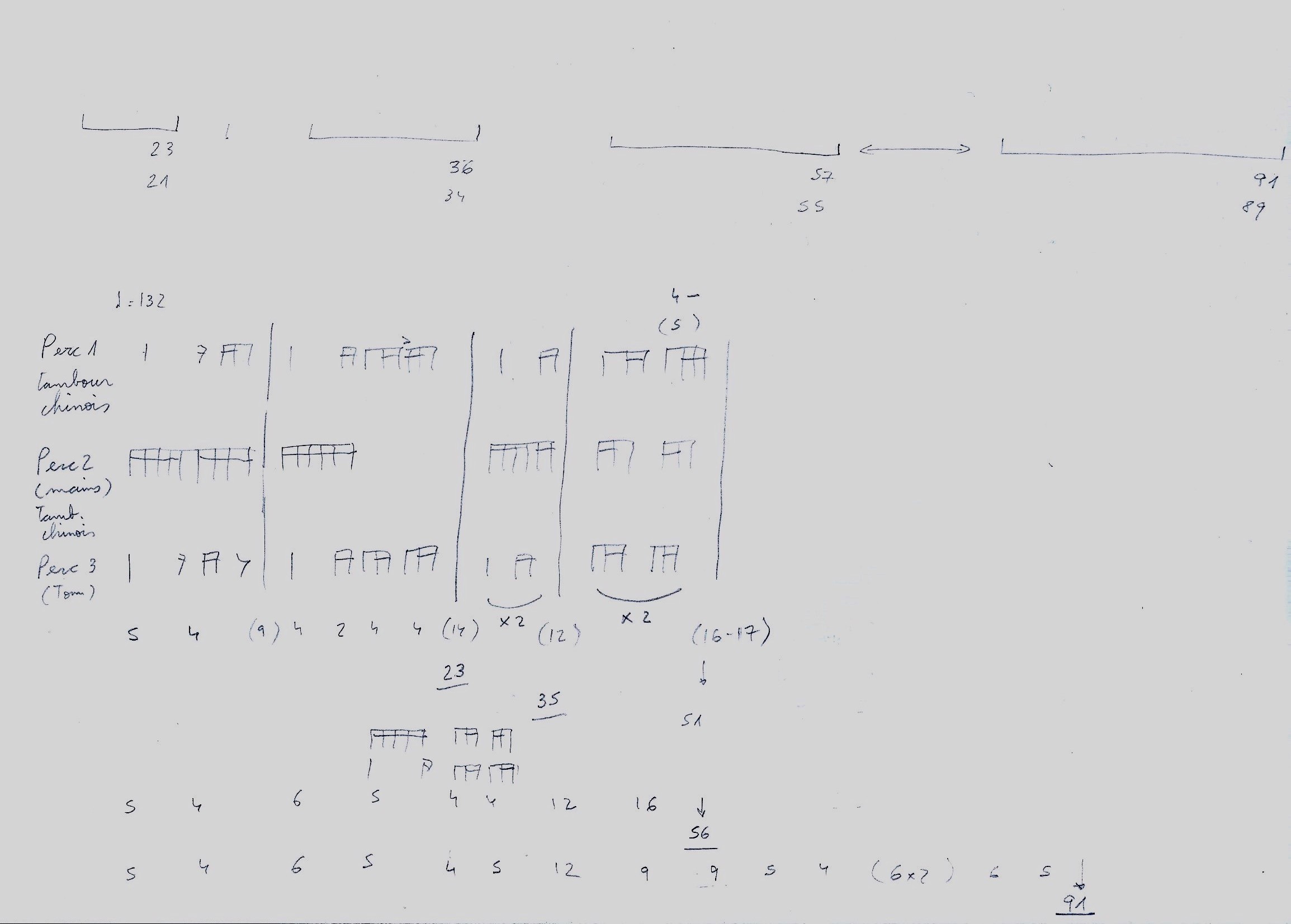

The work on temporal densification is also combined with the rest in this new piece: either through the addition of events or notes in a texture, which can generate chaos, or conversely through the creation of continuous textures, or created by acceleration, etc. The work using the Fibonacci series for these dense passages is explained by the desire to arrive at this idea of (geometric) accumulation in a precise or utopian way. The use of the Fibonacci series (see Figure 3) for these dense passages is explained by the desire to arrive at this idea of (geometric) accumulation in a precise or utopian (one might also say “mechanical”) way, in contrast to the process that develops in a more “organic” way (see Figure 4).

In several pieces, mathematical ideas or images (a field of strong inspiration also linked to my career) gradually become concrete in the work with sound material, in a sometimes artisanal way ”.

José L. Besada : « En raison de son intérêt pour la suite de Fibonacci, Giménez Comas s’inscrit dans la liste de compositrices et compositeurs des 20e et 21e siècles ayant exploité cet objet arithmétique comme source d’inspiration. Le cas de Béla Bartók est sans doute le plus cité, mais la méthodologie de recherche d’Ernö Lenvai, le premier à discuter cet aspect, a été mise en cause. En revanche, la suite de Fibonacci est clairement repérable dans quelques partitions de certains compositeurs que j’avais mis en jeu dans l’expérience cognitive de notre première rencontre. C’est le cas, par exemple, des accents du piano pour le début de Zyia (1952) de Xenakis –à l’époque, il travaillait dans le studio de Le Corbusier– ou du trombone à la fin du Solo pour deux (1981) de Grisey. De même, j’ai trouvé récemment à la Fondation Paul Sacher d’autres références plus subtiles à cette suite arithmétique chez d’autres compositrices ou compositeurs d’orientation spectrale : dans les esquisses de Jonathan Harvey pour Bhakti (1982) et de Saariaho pour … À la fumée (1990). Néanmoins, l’approche de Giménez Comas est, à mon avis, plus proche des manipulations de la suite trouvé par Giacomo Albert dans les esquisses de Brian Ferneyhough pour son Deuxième quatuor à cordes (1979-80). Tous deux montrent, de manière indépendante, une forme de convergence dans leur besoin de formaliser une ordination temporelle à travers les nombres ».

José L. Besada: “Because of his interest in the Fibonacci sequence, Giménez Comas joins the list of 20th and 21st century composers who have exploited this arithmetical object as a source of inspiration. The case of Béla Bartók is undoubtedly the most cited, but the research methodology of Ernö Lenvai, the first to discuss this aspect, has been called into question. On the other hand, the Fibonacci sequence is clearly identifiable in some scores by certain composers that I had brought into play in the cognitive experiment of our first meeting. This is the case, for example, of the piano accents at the start of Xenakis's Zyia (1952) - at the time, he was working in Le Corbusier's studio - or the trombone at the end of Grisey's Solo pour deux (1981). Similarly, at the Paul Sacher Foundation I recently found other, more subtle references to this arithmetical sequence in other spectrally-oriented composers: in Jonathan Harvey's sketches for Bhakti (1982) and Saariaho's for ... À la fumée (1990). Nevertheless, Giménez Comas's approach is, in my opinion, closer to the suite manipulations found by Giacomo Albert in Brian Ferneyhough's sketches for his Second String Quartet (1979-80). Both show, independently, a form of convergence in their need to formalize a temporal ordering through numbers”.

Find out more

- Editorial and list of Maths & Musique articles

- Núria Giménez Comas's personal page

- José L. Besada's personal page

- The BBVA foundation

Contact

BBVA Foundation

The work Pedres, llàgrimes sospeses by Núria Giménez Comas was commissioned thanks to the 3C-TEMPO project, financed by the Beca Leonardo a Investigadores y Creadores Culturales 2023 of the BBVA Foundation in Spain. The BBVA Foundation is not responsible for the opinions, comments and contents of the project, nor for the results thereof, which are the sole and absolute responsibility of its authors.