Quantum numbers? Surely you're joking, Mr. Feynman!

The ideas of quantum physics have had an enormous impact on the development of mathematics, influencing all its fields. Numerous notions have emerged, including quantum groups and algebras, quantum calculus and special functions. Numbers, the most elementary and ancient concept at the heart of mathematics since the Babylonians, should also have their place in the quantum landscape. In two recent papers, Sophie Morier-Genoud, professor at the Université de Reims Champagne Ardennes and Valentin Ovsienko, research director at the CNRS, both members of the Laboratoire de Mahématiques de Reims1 , have introduced a notion of quantum real numbers, or “q-numbers”. This work has aroused the interest of many researchers and has just been awarded the American Mathematical Society's David Robbins 2025 prize.

- 1UMR9008 - CNRS/Université de Reims Champagne-Ardennes

The starting point for the new concept of q-numbers, however, was not the work of Max Planck or Albert Einstein, but rather that of Euler and Gauss. Long before the quantum era, the work of these two titans led to the emergence of integer q-numbers, a theory at the interface of combinatorics and arithmetic. The famous q-binomial coefficients are the stars of this theory. They are polynomials of one variable (traditionally noted q ). The role of q-binomial coefficients in mathematics is immense, but they are also used by theoretical physicists. In physics, the parameter q is equal to eh, where h=6.62607015x10-34 (joules per second) is Planck's constant. Unable to remember the exact value of h and attracted by abstraction, mathematicians prefer to speak of h as an “infinitesimally small parameter”. However, the smallness of h in no way implies that its exponential q is close to 1! In mathematics, the parameter q can be of any « surrealist » nature, depending on the approach and theory. It can be real, or the root of -1, or a formal parameter, or a power of a prime integer.

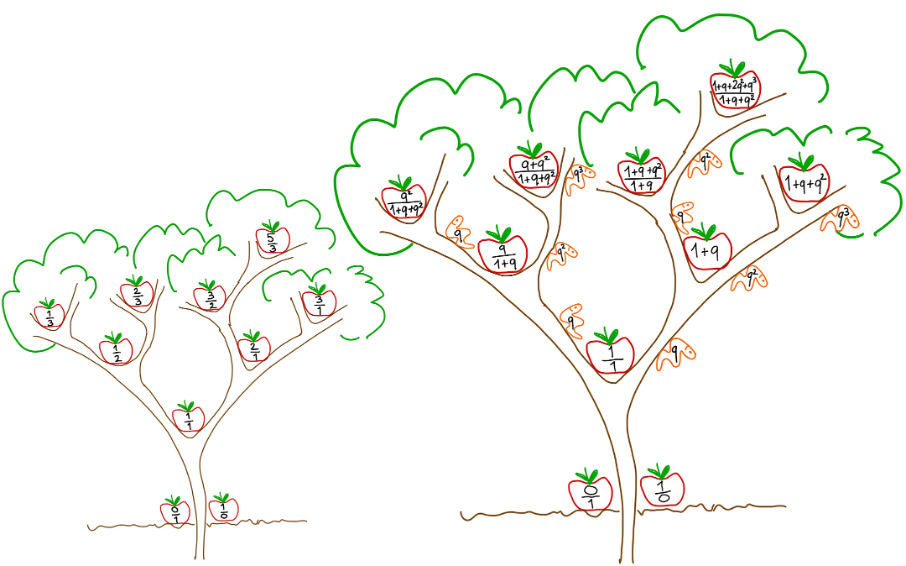

q-rationals bear a close resemblance to q-binomial coefficients. To define them, we simply replace Pascal's triangle with a binary tree, Farey's tree, in the definition of q-binomials. But there's also a big difference: q-rationals are rational functions in q. Another difference is the symmetry group, that fundamental notion in mathematics which is itself sometimes sufficient to define all objects. The symmetry group of q-numbers is the famous modular group, which also plays a central role in modern number theory. A pleasant and attractive aspect of q-rationals is their simplicity: they're easy to define and manipulate.

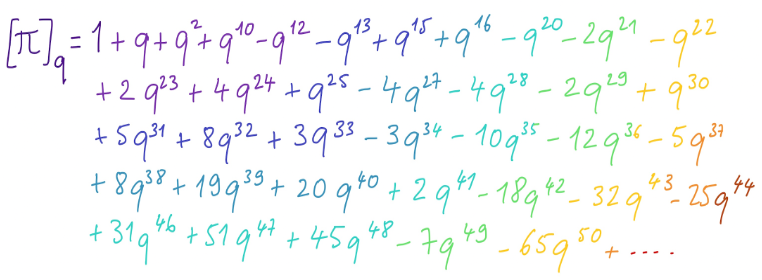

q-irrationals are obtained from q-rationals by convergence of Taylor series. These are q-series with integer coefficients, and not all their properties are yet known. For example, the interpretation of the coefficients of q-irrationals remains an enigma, especially the coefficients of the series that represents the number π.

The beauty of mathematics lies, among other things, in the synthetic versatility of its notions: the same formulas appear in different subjects to describe phenomena not related at first sight. Our protagonists, the q-binomial coefficients, are used in combinatorics to enumerate objects, in geometry to count points over finite fields, in mathematical physics to describe the quantum plane. This universality, difficult to explain, seems to be shared by q-numbers. Remarkable properties linking q-rationals to geometry, combinatorics and analysis have been demonstrated or observed by numerical experiments in several works. One of these properties is unimodality, the fundamental concept of mathematics. The first steps towards understanding the analytic properties of q-irrationals have been taken, giving applications to the classical theory of braid groups.

The theory of q-numbers is taking its very first steps, and has yet to be developed. The most important challenge is to understand the link to physics. But to do that, we'd first need to know whether Euler would have preferred to talk with Einstein and Gauss with Planck, or vice versa... Unless all four got together to send a thunderbolt and burn the q-numbers?! That chimera with the face of a baby and the tail of a monster!

References

S. Morier-Genoud, V. Ovsienko, q-deformed rationals and q-continued fractions. Forum Math. Sigma 8 (2020), 55 pp.

S. Morier-Genoud, V. Ovsienko, On q-deformed real numbers. Experimental. Math. 31 (2022).